About us

Our history

{{articleInView.title}}

Our history

Since 1927 Wellington Free Ambulance has been providing an invaluable service to the people of the Wellington region (and from 2012, the people of the Wairarapa region), thanks to the mayor of the day, Charles Norwood.

-

{{year.label}}

The man who started it all

Wellington Free Ambulance was founded by the mayor of the day, Sir Charles Norwood in 1927.

While out driving in his mayoral car, Sir Charles came across a man injured and cold, lying on the footpath in Lambton Quay.

“Has anyone sent for an ambulance?” he calls to the crowd standing around the injured man. The answer comes that none can be found, so Sir Charles takes off his coat, and lays it over the man while waiting for an ambulance from the Harbour Board.

This first act of kindness is what inspired the beginnings of your uniquely free ambulance service.

Sir Charles believed in a place where emergencies needn’t cost lives or money, declaring that his city would have a free ambulance service for everyone.

This vision was a gift that has held for 98 years.

Wellington Free head to help devastated Napier

At 10:47am on 3 February 1931, a 7.9 earthquake struck Napier and its surrounding districts, killing 256 people and injuring many more. It remains New Zealand's deadliest natural disaster.

Remembering the good times

When you're born in an ambulance it seems only natural to become an ambulance officer!

"In the early hours of a cold and wet Wellington morning an ambulance was dispatched to the then-distant suburb of Waterloo. The task was to pick up a pregnant woman and get her to St Helens Hospital in Wellington before she had her baby.

From what I was subsequently given to understand the ambulance driver (I believe his name was Paddy Buick) became lost and his arrival in Waterloo was much delayed. However, he loaded his patient into the ambulance and, accompanied by the woman’s husband, proceeded towards Wellington.

At some point in the journey Paddy was advised by the husband that the baby was coming. His response was 'well you do what you can there, and I will head for the hospital'.

A short time later and still in the moving ambulance the woman gave birth to a boy. The date was Wednesday 25 May 1938, and the baby boy was later named Ian John Henry Ross.

It is of course my contention that in some way or other this event created an interest in ambulance services and perhaps heralded my future career.

In 1959 I was invited to join the full-time staff at Wellington Free Ambulance by the then Superintendent Keith Smith. The total staff at that time was 15 Ambulance Officers plus the executive group of three. (K.Smith, E.Smith and J.Kimmins). There were only two stations – Wellington and Lower Hutt.

Over the next 17 years I held positions of Ambulance Officer, Shift Senior, Administration Officer and Deputy Superintendent.

After leaving Wellington Free I worked for the Wellington Hospital Board for a short period then was fortunate enough to be appointed as the Ambulance Advisory officer to the Ambulance Transport advisory Board, a position I held for 10 years. I then spent several years in an administrative role with St John Auckland."

– Ian Ross

Image: Ian Ross is front row first left, courtesy of A.W Beasley, Borne Free, 1995

Amy's ANZAC hero

Emergency Medical Technician Amy attends the Upper Hutt ANZAC Day service every year thinking about the ANZAC hero in her life.

The Second World War was the greatest conflict ever to engulf the world, taking the lives of 50 million people, including one in every 150 New Zealanders. Our population in 1940 was around 1.6 million.

New Zealand was involved for all but three of the 2,179 days of the war — a commitment equal to that of Britain and Australia. It was a war in which New Zealanders gave their greatest national effort — on land, on the sea and in the air — and a war we fought globally, from Egypt, Italy and Greece to Japan and the Pacific.

Amy, Wellington Free Ambulance emergency medical technician, will be attending the Upper Hutt Dawn Service on this year’s ANZAC Day to represent Wellington Free. However, Amy would be there anyway because service is in her genes. “I’ve marched at the Upper Hutt Dawn Service every year since I moved back to New Zealand 15 years ago.”

“I come from a military family. My dad, grandads and great uncle all served in the army. My grandad, Raymond Alfred Arthur Burnett, who falsified his age by 2 years to enlist, became a Prisoner of War during World War II. Whilst out on his patrol in Egypt he was captured by the enemy and became a POW for the remainder of the war,” Amy says.

“He survived his day of capture, a torpedoed boat and a number of years in multiple POW camps, he shouldn’t have survived but he did. He never spoke about his time in the army or what life was like at war until he decided to write his memoirs at the age of 80.”

Amy and her father Bill and sister Tash travel to Germany at the end of May to visit the Prisoner of War camp her grandad was released from exactly 75 years since the day.

Raymond is now 96 years old and Amy’s ultimate hero. “He’s always encouraged me to do what I want in life. Make mistakes, learn from them and move on. I wanted to follow in his footsteps and join the army too but what I do now is similar, helping people in need.”

Visit NZ History for more information.

Bring your kids to work day!

The 1940s didn't have the medical mannequins we have nowadays so what better way to practice first aid than on real people!

One-of-a-kind woman always been ahead of her time

Avid knitter, writer, Tai Chi student, and Wellington Free Ambulance supporter Audrey Harper of Upper Hutt lived in the UK in the 1940s, and was one of small group of women in the Women's Royal Naval Service (the Wrens) brought in to design ‘war game’ exercises for the Navy’s servicemen.

“We were never exactly told that our work was a new concept in teaching naval strategy using scenarios and exercise. In a way we were guinea pigs,” she says.

Audrey’s job was to work on a Perspex screen, plotting the presence of make-believe enemy ships, torpedo and bomb attacks, submarines and surface craft, all overlaid with fake weather conditions and time of day.

“Like a soap opera, events in an exercise came close upon each other to maintain interest and learning,” Audrey explains.

Technical information was passed over telephones (there were no computers back then) to the men on the course: ranges and bearings, visual sightings, reports from look-outs on the bridge or elsewhere. Audrey and the team expertly provided the information for trainees to absorb and strategise, and ultimately find a way out.

Women in England during WW2 once they reached 19 years of age either volunteered or were called up for war work. Audrey knows exactly how long she spent in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, a ‘Wren’, as the women were called.

“Two years, eight months, and 18 days. I know that because I used it to help make up the compulsory three years of service I needed to become a grade three teacher in New Zealand.”

She also remembers her 21st birthday.

“It was the best 21st I could have had. My birthday is August 13, and the war was declared over on August 15.”

Once discharged nearly a year later Audrey studied at Bristol University.

Every year on her birthday Audrey gives Wellington Free Ambulance a dollar for every year of her life, and asks her friends to make donations rather than buy presents.

She is also the woman behind the perfectly costumed paramedic teddies which are sometimes auctioned at fundraisers, and sometimes make their way into the homes of new Wellington Free babies.

Giving her life to helping others

Her devotion to helping people started in 1955 when Shirley Martin joined the Ladies' Auxiliary and stood on the streets of Wellington rattling a box for the free ambulance.

The Ladies' Auxiliary was a group of women who worked hard on getting the whole community behind keeping Wellington Free Ambulance free. Six decades later, she’s still very much at the heart of the organisation.

Shirley was 25 years old when her relationship with Wellington Free began. Close friends of founder Sir Charles Norwood and his wife, Shirley was recruited to be on the committee bringing with her bucket loads of passion and big ideas.

“It was about much more than filling the seats with bottoms,” she explains, “it was hard work.” She and the Auxiliary were responsible for raising every penny Wellington Free needed. “Unless we raised the money, we wouldn’t have ambulances or anything, so it was up to us to help the paramedics and get their new gear.”

The fundraising initiatives ranged from knocking on businesses’ doors to holding lavish events which were the talk of Wellington, and had people queuing to get in the door. “People knew who we were and what we were doing, so we had to be brave and go after the big money.”

Among Shirley’s highlights in the 50s was the first defibrillator the Ladies' Auxiliary were able to purchase. “And would you know it, the first time it was used, it was on one of my friends. It just goes to show you never know who will need the Free Ambulance,” she says.

Looking back, Shirley says she sees the Ladies’ Auxiliary as very small in comparison to today’s operations—but it was the first step, and those volunteers’ efforts ensured Wellington Free remained free to the communities they cared about.

Lady Norwood Rose Gardens

Lady Rose Norwood had a great love of flowers and was particularly interested in the development of the city’s parks and reserves during her terms as Mayoress of Wellington.

In loving memory of Sydney Barlow

The evening of Sunday 14 June 1964 saw the unthinkable happen at Wellington Free Ambulance.

Wahine disaster

On the morning of 10 April 1968, Wellingtonians woke up to gale force winds and torrential rain. Most people thought it was just another day in windy Wellington but with winter on the horizon.

Matamata Intermediate School reunion

On 5 July 1964 a class of 12 and 13 year olds from Matamata Intermediate School set off on a week-long adventure to the see the sights of the capital city!

The group of 33 students was supervised by their classroom teacher Brian Coomber and two supporting adults. For many of these children it was their first visit away from home, but they all had an excellent time! “The pupils loved the trip and it made a real impact on them” says Brian.

Part of their trip was to visit Wellington Free Ambulance, then based on Cable Street. The visit to Wellington Free Ambulance obviously had an impact. The children were especially impressed that ‘during the 24 hour off the men are allowed to leave the station’ and they especially liked that in-between calls the crew of the time could ‘play darts, billiards, cards and other games. In the dining room they have a TV set.’

The group of students stayed in contact over the years and this year the former classmates gathered in Wellington for a get-together, 52 years later! 18 former pupils, now aged 64 and 65 years old, arrived at Wellington Free’s Thorndon Station on a sunny Friday afternoon for a repeat visit and a moment of nostalgia. Class teacher Brian accompanied them on the trip and still managed to let them know who was in charge! The group was given a tour by Richard, one of our longest serving paramedics. Richard has been part of the Wellington Free team since 1970.

The group had an equally interesting visit this time round; although no official post trip report was written we managed to replicate their group photo 52 years later. Nice one Matamata Intermediate School!

Celebrating our volunteers

Wellington Free Ambulance has been relying on the kindness of volunteers for the past 90 years.

Volunteering in 1927 was very different to how it is now but the Men’s Auxiliary still formed an integral part of the service. With no official first aid training or authority to drive ambulance vehicles, honorary members of the team helped in a number of other ways. They double crewed with staff members to lend a hand at big incidents or multiple casualty cases. When not on the road with ambulance officers they helped on station, cleaning and sorting vehicles and equipment. When time allowed they had ‘first aid tuition’ from their ‘permanent’ colleagues and learnt about cases from the team who were actually there.

When Wellington Free started in 1927 the staff consisted of the Superintendent, who also acted as the secretary and organiser, six permanent bearers and 14 honorary bearers. We now have around 200 skilled and qualified paramedics.

Joining the Men’s Auxiliary and volunteering with the team was invaluable experience if you wanted to join the permanent staff. Denis Smithson joined the Men’s Auxiliary in 1967, volunteering for three years with the team before joining the permanent staff. He continued to work as an ambulance officer for over 40 years. You can read more about Denis’ experience as a member of the men’s auxiliary in the story about Sydney Barlow in this section.

Our volunteers have always been a generous and committed team who play a huge part in keeping the ‘free’ in Wellington Free Ambulance.

For information about volunteering and to find out how you can join the team, visit the volunteer page.

70s fashion and flare!

Richard remembers one novelty of the early 70s being the summer uniform – navy shorts and white walk socks.

47 years at Wellington Free Ambulance

At the end of June 2017, Wellington Free Ambulance said a warm-hearted farewell to Richard, one of our longest ever serving paramedics, as he embarked on his retirement.

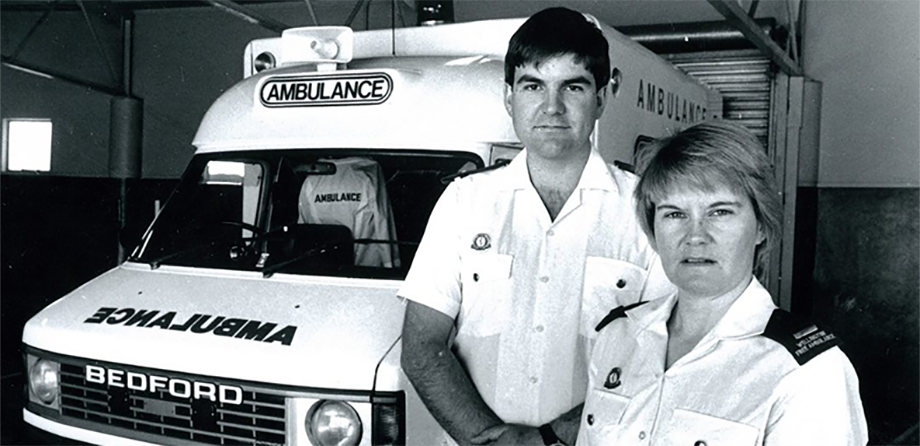

A career full of firsts for a passionate paramedic

"I've been employed for my brain, not brawn," says Marie Long (nee Larkin) Wellington Free Ambulance's first female paramedic.

Marie began her career in the ambulance service when she was 16 in 1969 as a volunteer in her home town of Featherston. She then went on to train at the National Ambulance Officers training school in Auckland.

In 1981, aged 28, Marie joined Wellington Free after being encouraged to become a professional paramedic by her tutors.

“It was never something I thought about because I did not know there were professional female paramedics. I guess they decided it was time a woman got involved.”

When asked about the challenges she faced, Marie said it was public perception more than anything.

“Initially I took people by surprise and it was just a matter of being professional and getting the job done."

“My colleagues were fantastic. As soon as they realised I was there because I really wanted to be an ambulance officer they were generous and supportive. I have very fond memories.”

Marie continued to have firsts during her career. She was the first female to be promoted to a Senior Station Officer as well as being the first female to manage an ambulance service. The Wairarapa Ambulance Service was part of the Wairarapa District Health Board before Wellington Free took over the contract. Marie’s career in the ambulance sector ended in 2005 when she moved into the disability sector.

Aside from saving lives, Marie also found love.

Marie met her future husband, David, at weekend handovers when they were both auxiliary officers. They became the first couple to train together as advanced care paramedics.

Marie’s husband still works for Wellington Free, and their daughters are heavily involved with volunteering for Hato Hone St John, one in Fielding and the other in Carterton.

Marie says that to become a paramedic, you’ve got to do it for the right reasons.

“It’s not about making a name for yourself, it’s about making a difference. You need to be prepared to put in the hard work.

“It was a fabulous stage in my life and I know I made a difference. I had a wonderful career.”

One-of-a kind Street Appeal

Thanks to you we've been responding to emergencies for 96 years.

The generosity of local people to support our life-saving services has always been incredible, especially on Street Appeal days! As volunteers line the streets with buckets in hand, the community has always dug deep and supported their free ambulance service. In 1982 our street appeal raised $25,484, a great achievement at the time.

Nowadays our street appeal has transformed into a bright and colourful event to celebrate our One-of-a-Kindness – Onesie Day! In our 90th year you raised an amazing $170,000! Onesie Day is always held in September. Check out our Onesie Day page to find out what’s happening this year.

A Royal opening

After 65 years at the Cable Street building, we moved to a new station which was opened by the Prince of Wales - now King Charles III.

Heartbeat Community CPR Training

Proudly sponsored by The Lloyd Morrison Foundation.

Wellington Free Ambulance’s CPR training initiative was set up in the early 2000s – designed to make Wellington the leading sudden cardiac arrest survival city in the Southern Hemisphere.

The Heartbeat Programme has come a long way since then. It is now proudly sponsored by the Lloyd Morrison Foundation and through training and education, Wellington is now statistically the second best city in the world to survive a sudden cardiac arrest.

Each week on average four people suffer a cardiac arrest somewhere in Greater Wellington and Wairarapa.

The chances of someone surviving cardiac arrest go up hugely when bystanders get straight into administering CPR, and keep on doing it until help arrives, alongside using an AED (automated external defibrillator).

Our Heartbeat programme can teach your workplace, community group or students CPR. Maybe that training will save the life of a friend, a colleague, or a stranger on the street. You never know when you’ll need it, so it’s best to be prepared.

To learn more about the programme visit the Heartbeat page on our website.

Patient Transfer Service

With reassurance and care, our Patient Transfer team has been safely and comfortably transporting patients since 2009.

Volunteering to help after the Christchurch earthquake

22 February 2011 - the earthquake that changed the lives of thousands.